The Samuel Williams Album Quilt

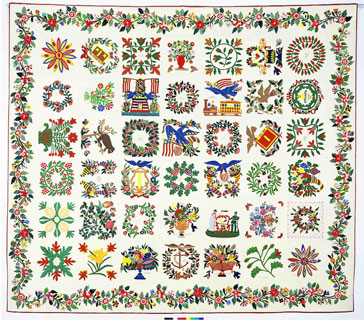

In October, 1999, in collaboration with The Baltimore Museum of Art, the Baltimore Appliqué Society began work on the reproduction of the Samuel Williams Album Quilt. The most ambitious historical quilt re-created by the BAS for the benefit of museums and historical societies, it is the product of thousands of hours of effort by over 100 volunteers working in the United States, Great Britain, and Canada. To produce this wonderful facsimile, members of the BAS carefully traced the motif of the original quilt using architectural Mylar to prevent any damage to the old fabrics. Templates for each segment (1200 pieces in the border alone) along with appropriate fabrics (selected from over 150 examples carefully matched to the originals for color and effect) were sent to members as kits. Once appliquéd, the finished squares and borders were returned, the inscriptions copied, the blocks joined, and the finished top backed and hand quilted in the same manner as the original.

For more information or to purchase the pattern set from the BMA at: Samuel Williams Pattern or call the BMA shop at 443-573-1844.

Funds derived from the Baltimore Appliqué Society's projects, such as the proceeds from the raffle of the Samuel Williams Reproduction Quilt and sales of this pattern set will be used to promote the preservation, conservation and augmentation of the BMA's quilt and textile collection. These resources have already made possible efforts to preserve and make accessible to the public the Museum's related archives -- the research and collected papers of early quilt historian Dr. William Rush Dunton.

History of the Samuel Williams Quilt

In 2002, Nancy Wagner Phillips and Carol Ann (Cappy) Phillips, daughter and granddaughter of Carrie Serena O'Laughlen Wagner, the donor of Williams-O'Laughlin quilt, spoke at a BAS meeting, discussing the shared memories of the family, the quilt's history, its exhibition and eventual donation to the BMA.They brought a copy of the family genealogy, which Cappy gave me along with a challenge to do more research.Here, at last, is what I have learned.--Debby Cooney

In 1999 the Baltimore Applique Society began working with the Baltimore Museum of Art to reproduce a quilt in the museum's collection to be raffled as a benefit for the museum's textile department.One of BAS's primary missions is to support the quilt collections of museums and historical societies.BAS members already had made raffle quilts for the Maryland Historical Society and the DAR Museum. Several members, including Jan Carlson, a founder and then president, spent many hours with Anita Jones, BMA's associate curator of textiles, to find a suitable project.They settled on the Samuel Williams quilt, one of the earliest and most elaborate Baltimore Album quilts.

Measuring 106” x 120.5”, the Williams quilt comprises 42 appliqued blocks surrounded by a wide border of three intertwined vines covered with flowers and leaves.Many of the most accomplished squares are grouped in the center; all are inscribed with the name of the person donating the square to the effort.Many of the signers are men, who surely had women make blocks for them.Few Baltimore Album quilts have as many blocks or signers as the Samuel Williams quilt. Several donated multiple blocks.This quilt is made of a relatively small number of fabrics, so the group making it shared the same sources or distributed the fabrics to a select few who then made the blocks. Several blocks of similar styles and fabrics are probably the work of the same hand or group. Dates in 1846 and 1847 plus wording are inked on the surface.The entire piece is finely quilted by hand.

The recipient of this masterpiece was Samuel Williams (1769-1847), a Baltimore native who worked as a merchant, a grocer, and as a lay minister with the Methodist Episcopal Church.Many details of his life surfaced in the research conducted in the 1940s by William Rush Dunton, Jr., published in his study, Old Quilts, and in the 1980s by BMA curator Dena S. Katzenberg and published in Baltimore Album Quilts.Historian Jennifer Goldsborough published a wide-ranging analysis Lavish Legacies in 1994 based on Baltimore Album quilts in the Maryland Historical Society.Other information is contained in Baltimore city directories, business directories, and the federal decennial census lists.

Son of merchant Samuel Williams, Samuel Williams, Jr., is first mentioned in the city directory of 1796 as a merchant doing business at 10 Bowley's Wharf. At some point he married Rebecca Cole and they had a daughter, Elizabeth.He continued to work as a grocer, sometimes working with other Williams, probably his brothers, until about 1822, when his listing changes to grocer and he acquires two new business partners.One business began at 162 Bridge Street with Thomas McLaughlin and moved to Dugan's Wharf by 1824. The large McLaughlin family (often spelled O'Laughlin, O'Laughlen, and variants) emigrated from Ireland in the late 18th century.The firm of Williams and McLaughlin existed until at least 1831, its last mention in the city directory.

In 1831 an obituary in the Baltimore American noted the death of Rebecca Cole Williams, wife of the Reverend Samuel Williams, on August 22 at age 57.The next year Samuel married Maria Bond Wehner, the widow of George Wehner, who had operated a dry goods store. Samuel was 63 and Maria, born around 1792, was about 40.At least two of Maria's three children were alive at the time:Harriet, married to John Armstrong, Jr., and Mary Anne, married to Michael O'Laughlin, son of Bryan O'Laughlin, who began doing business at the Bridge Street location around 1815.Thus the Williams-O'Laughlin connection continued even though the grocery firm did not.In 1833 Samuel is listed as a solo merchant; in 1835 he is again a grocer operating from Maria's address at 56 N. Gay Street.

A few details are known of Samuel's ministerial activities in these years.Newspaper obituaries mention funerals he conducted at the homes of the deceased and at his home.Dunton mentions that Williams taught bible classes at the Exeter Street M. E. Church.Dunton searched for but was unable to find any records of the church to learn more.During the 1830s and perhaps earlier, Samuel was the secretary of the Female Penitents Refuge, a city-sponsored charity of which the mayor was president ex-officio.The organization, with a typically Victorian euphemism for its title, probably aided reforming prostitutes (Baltimore, a port city, had its share) and unwed mothers. The refuge society had disbanded by 1837, but Samuel likely continued his charitable work in other ways.In 1840, according to Katzenberg, Williams and his friend Samuel Rankin attended the Methodist General Conference.These were meetings of bishops, preachers, and other church officials to set policies and practices for the denomination.Samuel's 1841 will begins with a reference to his position as a local elder in the Baltimore Methodist church.In those days lay members without appointed positions were not allowed to take part in annual and conference meetings.A reform movement to include lay members and elect church elders began in the 1820 and was strong in Baltimore.When the reforms were rebuffed the dissidents broke away to form another denomination.Samuel apparently did not leave his church to join the movement to bring more democracy into church practices.

The 1840-41 city directory lists Samuel only as the reverend, but by 1842 he was again in the grocery business, operating as Williams and Houlton at Exeter and Hillen Streets..By this time he and Maria had moved their residence to 157 N. Gay Street just behind the Exeter Street church.Williams and Houlton continued into 1845 and is listed as such in that year's city directory. Somehow Dunton missed Williams's 1845 business and personal entries and identified another Samuel Williams, an oyster dealer mentioned only once, incorrectly as the quilt's focus.By 1846 Samuel, now age 77, had apparently retired from business and is again listed solely as reverend.According to his obituary in the Baltimore Sun, Samuel died on April 21, 1847,“after a brief but painful illness”.Men only were invited to his funeral.

In his will, made at age 72, Samuel left his estate to Maria for her lifetime.He alludes to ownership of several small houses which, with his personal property, he believes will be enough for Maria's “comfortable support”.He does mention, however, a large amount of debt likely to burden the estate at his demise.He appointed Maria and his close friends John Armstrong and Michael O'Laughlin as his executors.After Maria's death the estate was to go to Samuel's only child, Elizabeth Collins, or her sons.

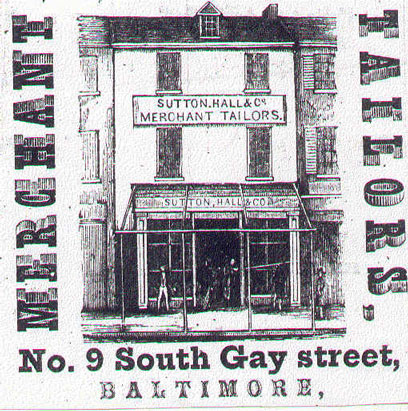

Maria Bond Wehner Williams, now widowed twice, was about 55 and living with her widowed daughter Mary Ann and three grandchildren. Maria had married George Wehner sometime around 1810; Mary Ann was born around 1811 and Harriet in 1813.George died in 1814 leaving a wife and three young children (the fate of the third child is unknown).The city directories do not mention Maria until 1824, when she is listed as a widow but had some kind of business.In 1829 she is listed as a “mantua maker” (seamstress) living at 56 N. Gay Street.Her next-door neighbor was Joshua Turner, who ran a grocery and feed store.Many of the buildings along this street functioned as residences and businesses (Figure 1). The Turners and Maria had a close association throughout their lives.

Maria married Samuel Williams 18 years after the death of her first husband; one can only imagine the difficulties she facing in raising three children alone.She may have met Samuel though her daughter Mary Ann's marriage into the O'Laughlin family, Samuel's partners in the grocery business.They also might have met through a Methodist church connection. After their marriage Maria moved into Samuel's residence at 32 N. Exeter Street.Between 1835 and 1842 the Williams moved twice, each time seeming to live closer to Samuel's Exeter Street church.Maria and Samuel were living around the corner from the church when he died. The house had been bequeathed to Maria and her sister by their grandfather.

After Samuel's death Maria moved her household to 63 N. Exeter Street.According to Jennifer Goldsborough's breakthrough discovery, Maria was making and exhibiting quilts there in 1850.The city directories in the 1850s continue to list Maria by with no occupation specified.By 1860 Maria, Mary Ann and her children had moved down the street to 57 N. Exeter.Maria died on October 13, 1863. Her will mentions a two-thirds interest in the house at 157 N. Gay Street as her only important asset.

By any analysis, Maria Williams was the organizing force in the making of her husband's quilt.The help of Mary Ann O'Laughlin and their extended family must have been crucial to such a complex project.It descended to Samuel Williams O'Laughlin, and eventually his granddaughter, Carrie Serena O'Laughlen Wagner.She donated the quilt to the Baltimore Museum of Art in 1985. There are so many O'Laughlins and associated names that the family always called it “the O'Laughlin quilt”.Both female and male family members, plus neighbors, friends, and church members contributed blocks.Neither Samuel Williams's daughter nor any other of his relatives signed the quilt, for unknown reasons.

The timing of the undertaking, recorded on blocks dated 1846 and 1847, suggests a presentation piece to Samuel for his lifetime of church and community work.However, Samuel died unexpectedly quickly in April 1847, and probably did not see the finished quilt.Blocks dated March 8 and March 9, 1847, suggest that he might have seen the completed top, but the elaborate border (as many BAS members can attest) and close quilting would have taken months to complete.But as preparations would have taken some time, Samuel surely knew that a grand effort to honor him was underway.

Several Baltimore Album quilts were made around 1850 for other Methodists ministers, some including a representation of the church building.While Methodists were not the only makers of elaborate album quilts, Methodist women in many congregations honored their pastors with such gifts.Most of the contributors to the Williams-O'Laughlin quilt were identified by Dena Katzenberg as Methodists. The number of donors who made their own blocks is subject to some speculation.Each contributor is identified by name penned in ink, in cross-stitch, or embroidery somewhere on the block.Katzenberg realized that the inked names were rendered in two styles of fancy penmanship only, meaning that the inscriptions were not the signatures of the presenters.

The Quilt's Contributors

Maria Williams

Maria (c.1792-1863) contributed three blocks that bear her name; all are relatively simple.One is well done sunflower in French fabrics; another is a single gracefully curved flower.The third is a simple flower wreath.Her name is misspelled on one block, which suggests that neither inscriber was part of the quiltmaking team.Maria's exact role in designing the blocks, setting them together, creating the border, and quilting may never be known.However, the years of work as a seamstress must have given her the confidence and expertise to plan and execute the most complex album quilt up to that time.

Mary Ann O'Laughlin

Mary Ann Wehner O'Laughlin (c.1811-1883) contributed two blocks to the quilt and probably those of her children.Those with her name include a large, folky racoon in a tree, and a dove holding a bible over floral branches; the latter is very well done (Figure 2).Maria Kate's name is on two very well made blocks.Her cherry wreath is very elaborate and dense with fruits and berries. The other, a multicolored cornucopia, spills out fruits, grapes and berries. Samuel Williams O'Laughlin, named for his step-grandfather, gave a simpler cherry wreath; Michael O'Laughlin's block is a spare wreath of honeysuckle.

Little is known of Mary Ann's life.Her father died when she was very young.She grew up in “old town” Baltimore and presumably learned to sew from Maria, who supported the family as a professional seamstress. Mary Ann was about 20 when she married Michael O'Laughlin in 1831.Their children were born in 1834, 1837, and 1839.Michael's name does not appear in the census lists or the city directories of the 1820s-30s, so his occupation is not known.He was successful at something, as he owned several properties around the city.

Michael O'Laughlin died in September 1839 at age 35.An obituary in the Baltimore Sun mentions a protracted illness; tuberculosis was a common killer of relatively young persons.He and Mary Ann were living at the corner of High and Hume Streets at the time.In his will Michael mentions his friend Samuel Williams as well as brothers John and David.Hebequeathed properties to his brothers in addition to providing for Mary Ann and the children.

Now widowed by with some assets, Mary Ann moved in with Maria and Samuel; the 1845 city directory lists a Mrs. M. O'Laughlin at 157 Gay Street.The nature of business is not given, but it was probably sewing.She was a member of the High Street M.E. Church and a supporter of the temperance movement, an important cause among Methodists at the time. She made a well-decorated block featuring a temperance fountain for a relative's quilt.Judging by the quality of her known output, Mary Ann likely designed and made quilt blocks and perhaps entire quilts with her household.She and the children were living with Maria on Exeter Street when Hannah Trimble visited in February 1850 to see a magnificent quilt being exhibited for public viewing. Her diary entry provides the only written evidence so far uncovered for the quilt work of the Williams-O'Laughlins and for Mary Simon. Mary Ann later moved a few doors down to 57 N. Exeter, where she died in 1883.

Mary Ann Hook

Maria's sister Mary Ann Bond Conn Hook(c.1796-1871) contributed two rather rough blocks.One is a vase of flowers with raw edges showing, signed in cross-stitch.The other is a wreath on a patterned background enlarged to fit the other blocks with her name embroidered.Mary Ann married William D. Conn around 1816.William is listed in the 1822-23, 1824, and 1827 city directories as an accountant with the Franklin Bank.He was probably dead by 1829 as his name does not appear in that year's directory.They had two children, Elizabeth born around 1817, and William, about 1824.An obituary for Elizabeth notes her passing in 1837 at the home of her uncle, Samuel Williams, who presumably conducted the funeral.Mary Ann, however, belonged to the High Street M.E. Church.The Conns had family and business ties to the Hooks; Mary Ann apparently married into that family in the 1830s.

At some point Mary Ann was widowed again; the 1842, 1845, and 1847-48 city directories list a Mary Hook, tailoress, at 28 George Street.Given the somewhat crude construction of her quilt blocks, this person may not be Mary Ann Hook.In 1850 Mary Ann and her son lived with Maria Williams on Exeter Street; by 1860 she had moved into Ann Lizzie Pattison's house.She died in 1871 at the home of her niece, Mary Ann O'Laughlin.

A. Lizzie Morrison

Ann Elizabeth Morrison was one of the orphaned daughters of Eleanor O'Laughlin, Michael's sister, and James Wesley Morrison.She was 17 or 18 years old when she made or otherwise acquired the tied bouquet with her name.The block is nicely done, so if Lizzie made it she received instruction on fine sewing from someone.She is listed in the 1850 census living with Maria Williams.She married Thomas Pattison, brother of Lizzie Pattison, in the early 1850s.By 1860 their household included three children as well as Mary Ann Hook.

Lizzie Pattison

Elizabeth Pattison contributed a well-done wreath of honeysuckle or passion flowers somewhat like Michael O'Laughlin's but more elaborate.She is listed in the 1850 census as 40 years old, living with her brother Thomas, 27, a grocer.

Lizzie Morrison

Probably related to Ann Lizzie Morrison, Elizabeth Morrison is probably the woman listed in the 1842 and 1845 city directories as Miss E. Morrison, dressmaker.Her block of an urn topped with a heart-shaped wreath held by birds shows great skill and color sense; it is an early example of the layered decorative elements that define high-style design developed in the city.The same block, some with her name and others not, appears on several other Baltimore Album quilts.The ring-handled urn takes on various shapes, baskets appear, and the flowers filling them increase and multiply, as her blocks found other recipients.

Lizzie must have achieved a considerable reputation as a quiltmaker or designer.She belonged to a group, perhaps a sewing circle, calling itself the Ladies of Baltimore. They made an exceptional album quilt for Lizzie, which is now at St. Louis Art Museum.She was a member of bible classes of 1848 and 1852 associated with the Charles Street Methodist Church, according to Katzenberg.

Katherine Wehner

Listed in the 1850 census as 43 years old, this Catherine Wehner was too old to be Maria's daughter.She was surely a relative of Maria's first husband George Wehner, perhaps his sister.Katherine's block is a nice wreath of oak leaves.

John Armstrong, Jr.

John Armstrong, Jr.was married to Maria Williams's daughter Harriet R. Wehner (1813-1835).A John Armstrong is listed first in the 1816 city directory as a shoemaker; listings continue for a boot and shoe manufacturer at various locations on W. Baltimore Street until 1848.With a 36 year history the business must have included John Jr.Obviously he remained close to Samuel and Maria after Harriet's death as he is one of the administrators of Samuel's will. His contribution to the quilt was a wreath of large buds and leaves.

Benjamin E. Bonds

The Bonds are likely to be relatives of Maria's as her maiden name was Bond. A Benjamin Bond is first listed in city directory of 1824 as a teller at the Franklin Bank (where William Conn also worked) living on Exeter Street north of Stiles. His listings continue through the 1842 edition. Another Benjamin Bond appears in the 1845 and 1847-48 directories, a property agent living on S. Exeter Street. This block is a graceful vase of flowers with layered blossoms.

Susan E. Bond

A Mrs.Susan Bond appears in the 1847-48 directory living at 116 Bank Street; she may be the widow of one of the Benjamin Bonds.Her block is a very high-style composition: a dove perched on a lyre encircled with floral sprays.An S. E. Bond gave a dove of peace enclosed in a classical-style wreath to a Baltimore Album quilt made in 1847 for Reverend and Mrs. Lipscomb of the High Street M.E. Church.This quilt has other blocks similar to but somewhat more complex than those on the Williams quilt. If Susan made both of these dove blocks,she joins the ranks of Baltimore top designers.

Samuel Kimberly

Listed in the 1842 city directory as a butcher living on High Street, Samuel Kimberly (1814-1856) appears in the 1850 census with wife Eliza (Bond) and a 17-year-old Thomas Bond.They are likely to be Maria's relatives.Samuel's block is a signature Baltimore Album quilt composition: overlapping flowers and buds of many sorts in a basket of thin bias-cut strips replicating a woven wire or wicker basket.Similar blocks are found on several of the best Baltimore Album quilts.Because of similarities of fabrics, they were probably made by the same hands.

Elizabeth R. Ellis

Elizabeth Riley(c. 1802-1883) married William Ellis in 1818.Apparently widowed, she is listed in city directories from 1842 to 1850 at 24 French Street.She was buried with some of the O'Laughlins at Green Mount Cemetery, thus is a relative.Elizabeth contributed an elaborate wreath of grapes and leaves surrounding an inked sketch of the “Holy Bible”.She made an identical square for an unfinished quilt dedicated to her mother; Mary Ann O'Laughlin made a temperance block for this quilt.

Stracey L. Hardisty

Stracey Susanna Brevitt was born about 1784 and married Henry Hardesty, Sr. in 1806.He fought in the War of 1812 with the 5th Maryland (Sterett's) militia.The 1820 census shows Henry and Stracey living near Samuel Williams in the 3rd ward. Henry is mentioned in the 1829 and subsequent city directories living at 81 N. Exeter Street; no occupation is given but he was a dry good merchant in old town.By the time of his death in 1848, Henry was living at 130 N. Exeter.Stracey is listed as still living there in the 1850 city directory and census.Her block is a basket of flowers cut from printed chintz fabric.This type of applique was old-fashioned by 1846, but probably familiar to the 62-year-old Stracey.The fabric might have come from Henry's store.

A.M. Hardisty

A.M. Hardisty's block is a fabric album book entitled “Friendship's Offering” encircled with flowers and leaves.Many album quilts have a variant of this figure to indicate the quilt's purpose. This one is done with Baltimore-style flair.The donor was more up-to-date with fashionable trends than Stracey Hardesty.A.M. might be one of Stracey's children; Hardisty/Hardesty was not a common name in the city at that time.Another possibility is Achsah Hardesty, a 52-year-old woman living in the 7th ward from 1845 through 1850.

Cassandra Dawson

Cassandra Dawson's sunflower is almost identical to Maria Williams's at the opposite corner of the quilt.She ran a store variously listed as dry goods and millinery from 1827 to 1838.The store is not listed under her name from 1840 on, so she may have sold it or gone under during the depression that gripped the country after the Panic of 1837.She appears in the 1850 census as Kassandra, 50 years old and living in the 4th ward with another family.If she managed to stay in the dry good business she might have supplied the fine French fabrics of her block, as well as some of the other fabrics used in the quilt.

Mary Myers

The railroad engine and car with an eagle and flag overhead is one of the most remarkable blocks on any Baltimore album quilt. According to Katzenberg it depicts the “one-armed billy”, a new type of engineering recently put into service on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad.The fabric pieces make a realistic depiction of the steam boiler puffing, a passenger car and its occupants, plus a patriotic symbol (Figure 3).An almost identical block appears on another Baltimore Album quilt in the BMA collection.The contributor might be Mary Elizabeth Myers, listed in city directories of 1840-41, 1842, and 1845 as a seamstress living at 203 N. Exeter Street. The location would put her near Samuel Williams's church and residence at the time.The 1850 census lists a 36-year-old Mary Myer living with Catherine Wehner in the 14th ward.

Maria Stevenson

Another close neighbor of the Williams family was Maria Stevenson, wife of Dr. James Stevenson, at 141 N. Exeter Street.Dr. Stevenson is listed in city directories at that address throughout the 1840s.In the 1850 census Maria is listed as 34 years old with four young children.Her block is a uniquely local piece: the monument in central Baltimore commemorating two battles of the War of 1812 that took place around the city.In the block the monument's column is decorated with a rope of flowers, flags, and eagles. This square shows up on other Baltimore Album quilts in the same fabrics and placement of elements.Its maker or makers produced them in kit form to be appliqued by other quilters.

E.M. Pettit

The Arms of Delaware block recreates the state seal of Delaware and its important pursuits--agriculture, shipping, and hunting--all of which were important in Maryland as well.Similar symbolic representations were published in advertisements for Baltimore businesses in newspapers and on labels.Pettit was an uncommon name, even in Delaware.Three Baltimore candidates for the square's donor have surfaced.An Elizabeth Pettit, wife of Moses, a shoemaker, lived in the 9th ward throughout the 1840s.A Mrs. Elizabeth Pettit lived at 104 Eutaw Street over the same years.The most likely candidate is Ellen Pettit, wife of Obadiah F. Pettit, owner of a book/variety store at 167 N. Gay Street.The location is a few doors from the Williams house at 157 N. Gay.The Pettits lived there from 1835 on.This Mrs. Pettit would have seen all kinds of publications with sources of inspiration for new-style, realistic applique.No Pettits with that exact spelling are listed in the 1840 or 1850 Delaware census; none of the Baltimore Pettits in the 1850 census was born there.E.M. Pettit also contributed a realistic depiction of a hunter in a framed landscape to an exceptional album quilt of 1847-50, with blocks also given by Lizzie Morrison and Agnes Rankin.

Samuel Rankin, Arrianna Rankin, Agnes Rankin

Samuel Rankin (1789-1857), born in Ireland, was operating as a grocer in Baltimore by 1824 at Potter and Gay Streets, old town.By 1845 he lived at 157 N. Chestnut Street. He and Samuel Williams were in the same business and held appointed positions in the Methodist church.Samuel Rankin must have been an elder as he attended the General Conference of 1840.Rankin's recorded religious and charitable work was impressive.By 1842 he served as city-appointed“manager for the poor” of the 5th ward, a position he held for many years.He also was a trustee of the Baltimore Almshouse, which served 500 of the city's destitute.Language in obituaries suggests he may have undertaken ministerial functions as well.Samuel must have been a great friend of Williams, as he and wife Arrianna ((1797-1878), daughter Agnes (born c. 1822), and two other Rankins contributed to the quilt.

Samuel Rankin's eagle block presents another favorite Baltimore image.Poised in the center of the quilt, an eagle with gracefully posed wings holds a liberty cap and flag in his claws and swags of flowers in his beak.Shaded blue fabric is used to great effect on his body.Eagle blocks in the same fabrics and pose appear on several other Baltimore Album quilts, as do less lavish versions. Arrianna Rankin, Samuel's wife, contributed a graphically pleasing four-cornered assembly of pineapples.Their daughter Agnes Rankin's block is four flower-filled cornucopias, smaller versions of the single horn in Maria Kate O'Laughlin's block.Many of the fabrics and placements are the same as those of her father's block.Agnes also contributed a lavish bouquet block to the same 1847-50 album quilt with blocks from Lizzie Morrison and E.M. Pettit.

Susan Rankin, Esther Rankin

The identities of Susan and Esther Rankin are less sure, but they may also be daughters of Samuel and Arrianna.The 1840 census lists two young women in Samuel Rankin's household (women were not named individually until the 1850 census).One was Agnes, the other was likely Susan or Esther.Susan's name was on a class list at the North Baltimore M.E. Church in 1842, along with J. Creamer and Elizabeth Sliver.Susan's block is another favorite Baltimore Album composition of fruits and berries overlapping in a fondu-fabric compote.Its shares the fabrics of the eagle and several other blocks.The fruit compote here is more realistic looking than those on quilts just two years older, suggesting a rapid evolution in designs as more and more album quilts were completed.Esther Rankin's leafy, cut-work block is a more generic album quilt design.

Agnes Bryson

Agnes (born c. 1823) was the daughter of James Bryson, a clerk at the Merchant's Bank since at least the mid-1830s and living in the 6th ward.She was 27 in 1850 and living with her father and siblings.An 1837 obituary for a Mrs. Margaret Bryson notes that she died at the home of Samuel Rankin at age 68.James Bryson was a widower by 1850 with a daughter Margaret.The older Margaret Bryson was 11 years older than James; she might have been his sister.His daughter Agnes gave a cut-out chintz applique, a stylistic throw-back to 1820s and an unusual choice for a young person.It is set on the opposite side of the quilt from Stracey Hardesty's chintz basket in the same row.

Eliza C. Bryson

Eliza (born c. 1816) was the wife of William J. Bryson, living in the 3rd ward in 1850 with a young son.William's occupation is not listed in the census or in the 1847-48 city directory. He appears in the 1850 directory as a steamboatman. In 1831 a William J. was listed as a grocer at Hillen and Potter near fellow grocer Samuel Rankin.Eliza's block is four cornucopias surmounted by a blue spread-winged eagle holding a shield.The fabrics and construction are the same as those of Agnes Rankin's block.

Thomas K. Turner

Thomas (born c. 1812) was a house and sign painter first listed in business the 1840-41 city directory.He and Samuel Rankin ran adjoining advertisements for their businesses in the 1845 directory (Figure 4). By 1846 Thomas, his wife Martha and their two children were living at 163 N. Chestnut, three doors from Samuel Rankin.His contribution is a graceful dove encircled by well-done oak and acorn wreath.The oak leaves in this composition resemble those on the border. The circular wreath enclosing a bird, lyre, or other motif became a staple in the best Baltimore Album quilts after its appearance in the Williams quilt.Thomas is likely related to the other Turners on the quilt.

Mary Turner, Susan Turner

The Turner's association with the Wehners, O'Laughlins, and Williams went back to the mid-1830s, when then Maria Wehner lived next door to Joshua (1776-1841) and Susanna Mumma Turner (1786-1854) on N. Gay Street. Joshua and his sons ran feed, lime and grocery stores in several locations.Maria may have been related to the Turners as she lived next door to them at two different times. The elder Michael O'Laughlin's mother was a Mumma, so he and Susanna had a family connection. Joshua died in 1841, still living at 58 N. Gay.By 1845 a William H.H. Turner was operating a feed business at 159 N. Gay Street, next door to the Williams house.Susanna Turner lived there from at least 1846 until she died in 1854.

Mary (Brown) Turner (born c. 1819) married Francis (1818-1858), son of Joshua and Susanna Turner, in 1839.He had worked in the family feed and grain business since the 1830s. They lived with the elder Turners at Exeter Street, then at 30 Harford Avenue in the 3rd ward.Mary's block is a simple floral spray enclosed in a fabric circle with tulip accents on the rim.

Susan Amanda Turner was Francis's sister; she probably lived with her mother on Gay Street in the mid-1840s.Her handsome, one-of-a-kind block encloses a funeral urn in a laurel wreath with the letters WATSON intertwined.The block honors Baltimore's Colonel William H. Watson, killed in the Mexican War Battle of Monterrey in October 1846 (Figure 5).The Turners were members of the Exeter Street M.E. Church; other Turner relatives, the Creamers, attended classes at the North Baltimore Station with the colonel's mother, Rebecca Watson. The war produced an outpouring of patriotic sentiment across the country and in Baltimore, which lost Colonel Watson and Major John Ringgold in the conflict.

Margaret L. Brown, Helen Brown, Ann Brown

Margaret L. and Helen Brown were sisters of Mary Brown Turner. Margaret's square is one large stem of flowers; Helen's is leafy flowers in a two-handled pot.Both are rather spare compositions in contrast to many of the others.Ann Brown is probably related to the other Browns.An Ann B. Brown lived at the corner of Exeter and Salisbury Streets all through the 1840s.She may be the same Ann Brown listed as a mantua maker in 1837-38.Her gift was a simple wreath of leaves, a design found on many album quilts.

Jane L. Creamer

Jane L. Brown, another sister of Mary Brown Turner (born c. 1820), married Thomas Creamer (1816-1875), a lumber merchant, in 1840. They lived at 140 Monument Avenue in the 2nd ward with five young children.She may be the J. Creamer on the same class list at the North Baltimore Station as Susan Rankin.Her husband Thomas worked with his father Joshua and brothers David and William in the family lumber firm.Jane's block is a squarish tulip wreath.

Sarah R. Creamer

Sarah (born c. 1828), a daughter of Joshua Creamer, head of a lumber firm with offices in two locations, was Jane Creamer's sister-in-law.In 1850 Sarah was 22 and lived at the family home at 135 N. Exeter Street, close to Samuel Williams's home and church.Her block is square wreath with flowers and fleur-de-lis similar to others on the Brown-Turner Album quilt discussed below.

Edward Rossiter

Edward Rossiter does not show up in either census or city directories.He had some connection to Baltimore, as his contribution is a symbol of Baltimore's maritime position.It shows an anchor and chain circled by a floral wreath and topped by a spread-winged dove. The anchor is also a religious symbol of hope, so there is probably a Methodist connection.Rossiter must have obtained his square from someone in the O'Laughlin circle as it shares fabrics with many others.

Contributor's Circumstances

As many quilts scholars have noted, donors, makers, and recipients of Baltimore Album quilts tend to be solidly middle class and often, though not always, Methodists.With its emphasis on reading and understanding the gospels, Methodism demanded a high degree of literacy.It also requires a substantial commitment of time to attend Sunday and weekday classes along with worship.Those involved in the making of the Williams-O'Laughlin quilt fit the profile handily.Dena Katzenberg identified most of them as Methodists.Members of Samuel William's Exeter Street church included his family, the Browns and the Turners, and probably most of the donors living on Exeter and Gay Streets near the church.Other donors attended the High Street M.E. Church and the N. Baltimore Station.

Occupations of the male donors and husbands of the women donors include grocers, a butcher, a painter, several store owners, a doctor, lumber merchants, and bank clerks.Women with occupations known generally were widows and worked as seamstresses, dressmakers, or shopkeepers. A few of the donors were relatively wealthy.The 1850 census lists the real estate of Dr. James Stevenson at $20,000, the widowed Susanna Turner at $20,000, the widowed Stracey Hardesty at $15,000.

Most of them lived in the 3rd, 4th, and 5th wards near the harbor, called old town Baltimore.These streets were among the earliest mapped out and were lined with modest three-story houses that served as businesses and homes.Most downtown residents lived in close quarters with each other and with free blacks, as well as some slaves.Many of the donors had servants to help with their household tasks, children and possibly with the sewing of blocks, tops and quilting.In 1850 the census taker recorded the name of the head of household, the wife and children, then boarders and in-laws; servants were listed last.Also recorded was age, race, place of birth, value of real estate, student status, and absence of literacy. (Slaves were recorded on a different form.)Maria Williams employed two black women, Dianna Irons, 50, and her daughter Ann Maria, 25, who lived with the family of eight adults and children.Francis and Mary Brown Turner, who had three young daughters, also employed a black woman and her daughter.The painter Thomas K. Turner and his wife had two small children and a black woman in their modest household.Dr. James Stevenson was wealthier; he and his wife employed three unrelated females: a white woman and a black woman, both native-born, and a Scotswoman.

Young Sarah Creamer lived with her parents, siblings, one black and one white servant.Jane Creamer, her husband and five children had two black women living with them. Agnes Bryson's mother had died but the nine Brysons ran their household with two Maryland-born white women.Samuel and Eliza Kimberly had two children, a young relative and Bridget, a 19-year-old Irish girl; she was probably an early refugee from the devastating potato famine that began to decimate Ireland in 1845.Samuel and Arrianna Rankin employed a young German woman.Baltimore was a magnet for immigrants, especially from Ireland, Germany and Scotland.Increasing numbers of arrivals led to the rise of the anti-immigrant “Know Nothing” political party, which became very strong in Baltimore and the rest of Maryland. in the 1850s.

The Brown-Turner Album Quilt

Aside from the O'Laughlin family and neighbors, another distinct group's contribution was notable--the Turners, Browns and Creamers.As mentioned, many of the Turners lived and worked next door to the Williams on Gay Street from 1842 on.Members of that extended family worked on an album quilt of their own at the same time as Maria Williams and the O'Laughlins in 1846.It is now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.The museum believes that Susanna Turner made her own and at least three other blocks; her daughter Margaret also made and inscribed at least three.Most of the blocks are generic album quilt compositions-- wreaths and pots of flowers of a few pieces and little layering.

Susan Amanda Turner's floral wreath is more accomplished with various flowers, some layered, joined at the base with a knotted bow. Mary Ann O'Laughlin contributed the blue eagle with flags and garland that became the quilt's center.It is virtually a duplicate of the center square of the Williams quilt, signed by Samuel Rankin.Lizzie Morrison gave an almost identical urn with heart-shaped wreath and birds, this time signed more formally, “Elizabeth Morrison”. Mary Ann Hook made two more rather rough squares for this effort.

Eight members of the Turner clan gave blocks to the Williams-O'Laughlin quilt--Mary Brown Turner, Susan Amanda Turner, Thomas K. Turner, Helen Brown, Margaret L. Brown, Ann Brown, Jane L. Creamer and Sarah R. Creamer.Many of their blocks are very similar on both quilts.While colorful and well done, these less elaborate blocks were set around the more complex central section.Only Susan Amanda's Watson urn shows stylistic innovation.

The Brown-Turner blocks probably were made for Mary Turner, but they were not joined into a quilt until the 1860s or later.In contrast the Williams-O'Laughlin quilt had a more public purpose. It was a tribute to a deceased Baltimore notable, and shows pride in local achievements--the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad and maritime culture. It includes many patriotic symbols--flags, shields, and war monuments. The racoon was the symbol of the Whig Party, which pressed for the annexation of Texas.The quilt makes obvious the upsurge of nationalism that carried the war's best-known general Zachary Taylor, and the Whig Party, to the White House in 1848.Finished in late 1847 or 1848, the quilt likely was exhibited at Maria's home or in some public place.Its makers had developed a new type of realistic-looking applique and had created the most intricate possible border comprising thousands of individual pieces.Some of them were making multiples of their blocks, refining and improving them in successive attempts. Such a quilt deserved a public viewing, and imitation.

I am greatly indebted to Carolyn Bracken, historian and genealogist of the O'Laughlin, Morrison and Pattison families.A descendent of Bryan O'Laughlin and Ann Lizzie Morrison's sister Molly, she has researched Baltimore history for years. She shared her vast amount of information with me; without it I would never have found many of these figures.

Figure 1. An 1845 advertisement for a business in old town Baltimore, near where Maria Williams and the Turner family lived and worked.

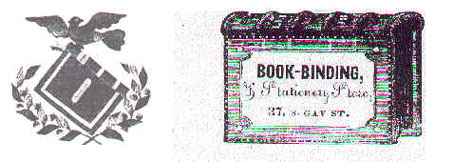

Figure 2. Mary Ann O'Laughlin's Bible block and a local advertisement.

Figure 3. Sketch of a train in a business directory and Mary Myers's block.The engine and car in the block are the reverse of the direction in the illustration.Did the maker cut out the illustration to use as a pattern, lay it on the cloth and cut?

Figure 4. Adjoining advertisements in 1845.

Figure 5. Susan Amanda Turner's Watson block used a familiar image of a funeral urn for inspiration.

©2004 Debby Cooney, Baltimore Applique Society>